Editor's Note

A DBQ (Document-Based Question) is a teacher-created packet of primary and secondary sources that illustrates various perspectives on an event or movement. Students construct an argumentative essay or answer a series of questions with evidence from the documents. At Menlo School (CA) the Upper School History Department has revised this assignment to a DIY-DBQ in which students become the curators and designers of a DBQ that can be given to another student.

Why a Student-Designed DBQ?

At the beginning of the second semester of 10th-grade U.S. History, teachers begin preparing students for a major history research paper that will be written later in the year. One assignment is to create a DIY-DBQ that examines a topic from multiple viewpoints.

When historians construct an understanding of the past, there are considerable differences in their interpretation. The goal of this project is to have students design a learning experience for their peers in which they wrestle with how to refute or support a particular viewpoint. In the dual role of content creator and student researcher, students develop their capacity to reason flexibly. By focusing on the process of interpreting historical evidence, DIY-DBQ prepares them to write a strong historical argument paper in the spring.

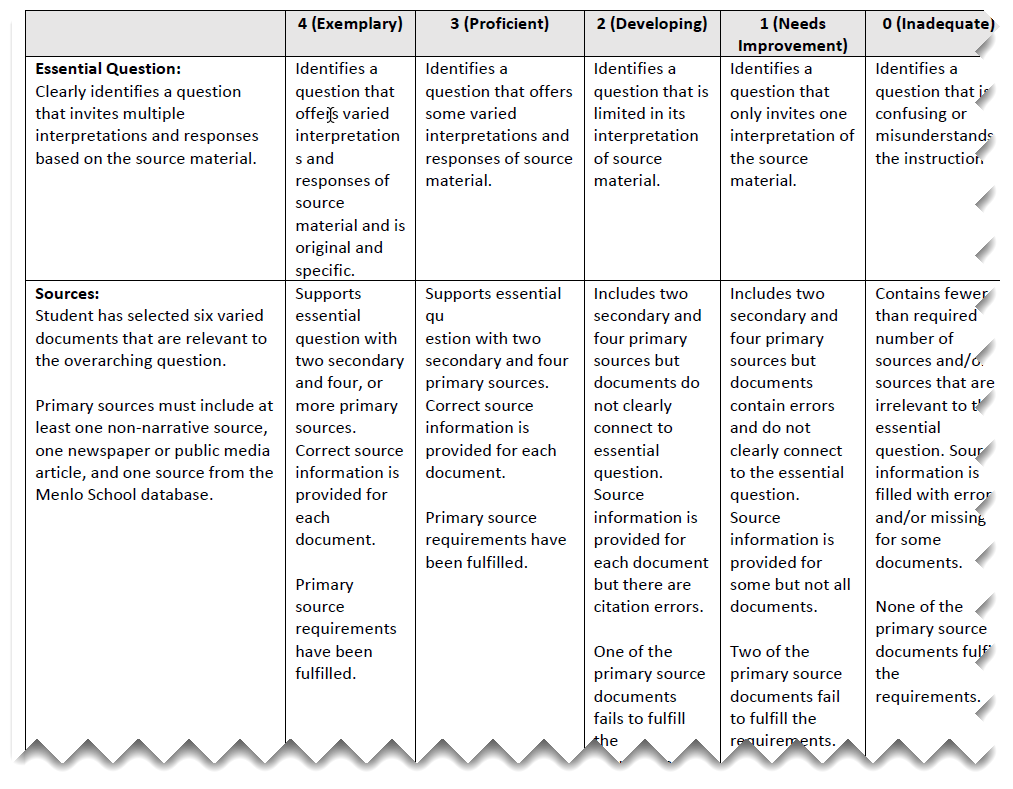

A Do-It-Yourself DBQ and Rubric

Guided by the accompanying rubric, you will create your own version of a DBQ, a do-it-yourself, hence DIY-DBQ. Similar to the document sets you referenced and addressed in your previous essays, you will now create one of your own for the study of World War II. You will have the better part of three class periods next week for this activity as well as your homework assignments for the next three classes.

The DIY-DBQ begins with your question or prompt, one that could reasonably be answered in different ways based on reference to documents. You then provide a total of six varied documents, each source with a citation, introduction, and a series of questions about it. The final day of this project will be dedicated to an exchange of DBQ assignments from which we will learn about WWII by reading and responding to our peers’ questions and sources.

Using Sources Responsibly

Our students are accustomed to creating Chicago-style citations in NoodleTools. The project creates opportunities to work through some complex source citations, as well as to review some problem source types they’ve encountered previously. Students are encouraged to “save everything”– to keep any document that has potential – initially bookmarking it with a minimal citation.

Once the DIY-DBQ set is finalized, unneeded sources are deleted from the reference list (sources can always be restored) and full entries are polished for the project’s references. I create a NoodleTools Project Inbox for each class and share it with the teachers. Everyone can comment on the quality and accuracy of students’ sources.

Logistics

I revisit the relevant research guides, make needed updates, and address any changes or glitches when I’m emailed by one of our sophomore-history teachers announcing that they are about to begin the project.

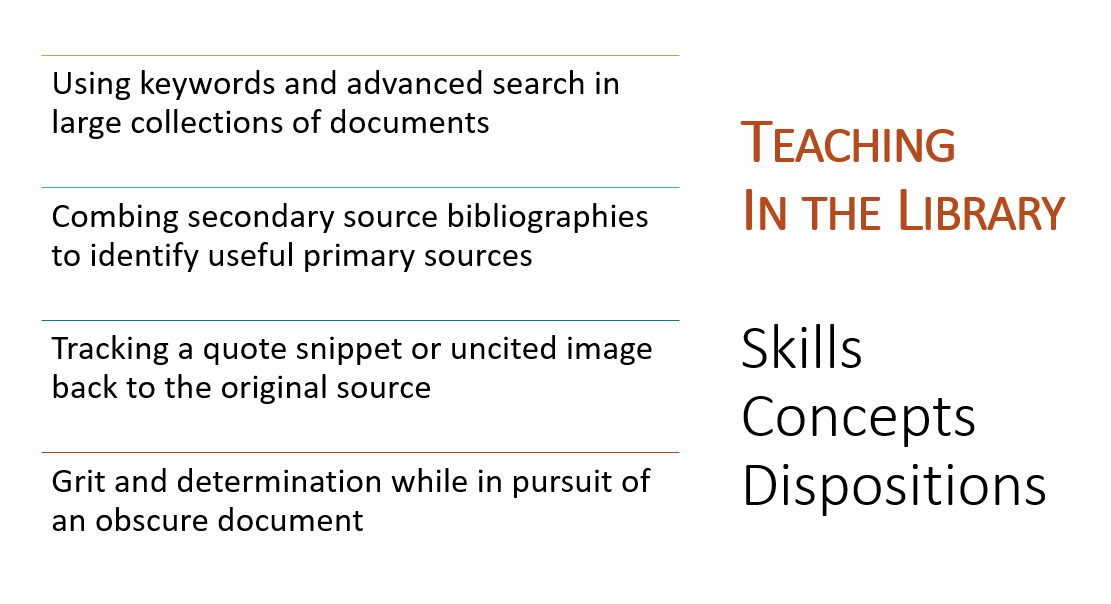

We schedule 2-3 visits in the library classroom, sufficient time to learn to use the new resources and review citation specifics. I spend the first 10-15 minutes of each class on instruction, answering any general questions about the project. The majority of time is devoted to working on their research.

We also work individually with students. I meet with them at other times during the school day, and I am available via email or Zoom until 10 pm most weekdays. I encourage them to make weekday meetings a priority since I’m only sporadically available on weekends.

Since students have shared their work with me via a NoodleTools Project Inbox, I’m able to monitor their progress at the end of each class, and assess their selection and understanding of the documents they curate thoroughout the project.

From Exploration to Focus

Tertiary Sources

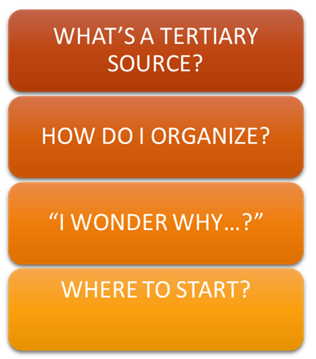

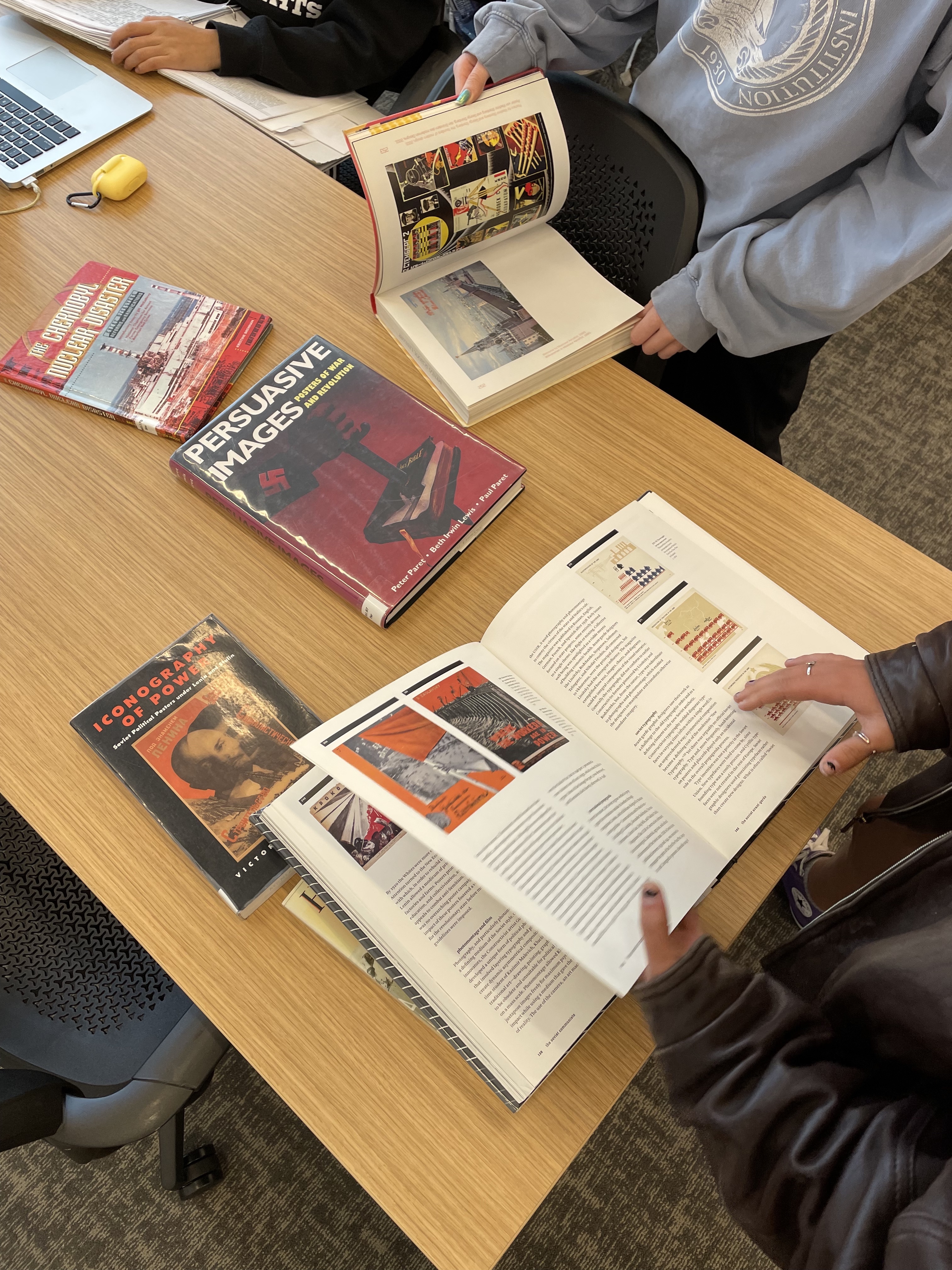

Students begin by doing a tertiary investigation related to World War II. Some have clear interests but others need to explore topics by reading background articles and browsing library books. Many want to rush through this step as they don’t feel they are “doing anything.” We emphasize that a thorough presearch prepares them to identify and locate the most relevant and compelling documents for a focus that intrigues them. Since students have a tendency to start with a Google search, I show them relevant library books at this early stage.

In our first class, we discuss the nature of a tertiary source and share examples. (I always dare them to add Wikipedia which is, for this purpose, an acceptable tertiary source.)

I explain the value of keeping a running “for my eyes only” document with a list of relevant vocabulary: keywords, search terms, dates, places, people, and events.

As this is a presearch, I encourage them to explore with open-minded curiosity and brainstorm: “I wonder why…”

Finally, I demonstrate — and then watch them — search the library catalog and find a book on the shelf.

Secondary Sources

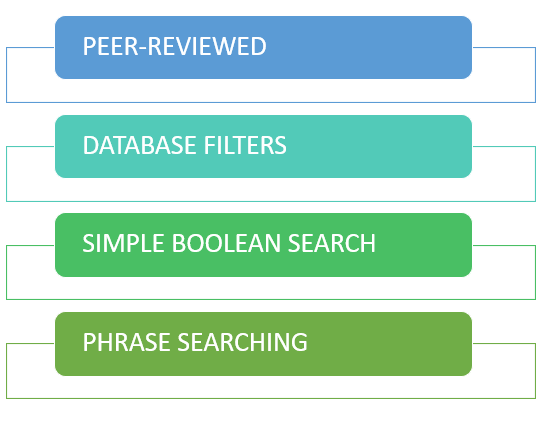

For peer-reviewed sources, we steer them to JSTOR and Academic Search Premier (EBSCO) — databases they’ve used in previous projects. They explore secondary sources, looking for areas in which historians have disagreed, a topic or question which they might reinterpret and argue in different ways. Students are asked to analyze the arguments made by individual historians and ascertain gradations of differences within various interpretations.

Finding secondary sources in a database is challenging but, by refining their search skills, they’re learning to “speak” to each database in its own language. Using the Advanced Search interface, we discuss search terms (I urge them to “think like a thesaurus”), phrase searching and simple Boolean logic. Then I demonstrate how the interface allows them to filter results. Lastly, I model reading comprehension skills that help them reason through relevance determinations.

primary Sources

Next they need to locate various types of primary sources that illustrate aspects of their argument and are open to interpretation. One must be a visual source such as a poster, graph, chart or political cartoon. I introduce AP Images (EBSCO) and Image Quest (Britannica) as well as a relevant set of curated primary sources from our extensive WWII LibGuide. Students are encouraged to consider what type of document would be most useful or informative in their DBQ and then to search for that document, rather than asking “where can I find a primary source” without giving thought to what they are looking for.

Students are gaining an increasingly complex understanding of historical research.

Learning Challenges

One of my challenges is helping students to distinguish between secondary sources in academic databases and tertiary sources on the open web. When we first move to the secondary-source step of the research process, I explain the peer-review process, often inviting the teacher to explain his/her own experience in publishing a research paper. This serves two purposes. Students gain understanding of a term they’ll hear in other contexts besides history class, since peer-reviewed resources are used in both English and science classes. In addition, they begin to appreciate that these skills apply to future academic endeavors, just as their teachers have done.

Students often begin with an internet search despite having been told that secondary sources are much more easily found in our databases. Rather than confront them immediately, I monitor their bibliographies in NoodleTools and intervene after they’ve collected a couple of sources but before they’ve invested time in annotating tertiary sources or polishing website citations. At this “sweet spot,” they’re more willing to tackle academic databases and can process the distinctions and make comparisons. When writing their annotations, students are expected to explain why a source is relevant and authoritative. They do a quick search on the author(s) to see who they are and what else they have published, which also helps them differentiate a secondary source from a tertiary source.

Another challenge is helping students craft a debatable question. Menlo School’s Upper School History teacher, Peter Brown, theorizes that students “don’t know enough to know what is debatable” while the History Chair, Carmen Borbón, claims that this is how novice historians think: they create a yes/no question by default, recognize that this is problematic, and then revise their question to ask for nuanced thinking.

The most effective way to deal with these challenges is for us to circulate through the library and conference with students. We provide individual guidance on how to use particular resources to help frame the question and how to turn closed questions into open-ended inquiry. We’re all learning from participating in this integrated instructional partnership.

Making Their Thinking Visible: The DIY-DBQ Set

To create a DIY-DBQ, students write a description of each source and provide contextual information about its origins (e.g., who is the author, when and why it was written). They craft analytical questions about each source that will encourage their peers to think deeply about the issues involved in the topic.

Next they test the effectiveness of their work by answering their question(s) for one source and revise their work as necessary. As a form of self-assessment, they write a short analysis of how the source could be used to answer their questions.

The strongest documents are a vehicle for multiple interpretations and the best explanations highlight the diverse ways in which the document can be used. By explaining their thinking process explicitly, students uncover shades of meaning that were not evident initially.

A Good Intermediate Step to Historical Thinking

Curating primary-source documents for a DBQ involves another way of thinking about sources. A document doesn’t answer a question; the student’s interpretation of various ideas and evidence within sources creates the meaning. History department chair Carmen Borbón appreciates the opportunity for students to understand different perspectives in documents and to learn how that perspective can shape their own arguments. “I think of students ‘shining a flashlight’ on a fragment of a past event or movement in order to test their theories about its context and meaning.” Peter Brown explains: “This is an approximation of the work that professional historians do, but without the long commitment of a full research paper. It’s a good intermediate step.”