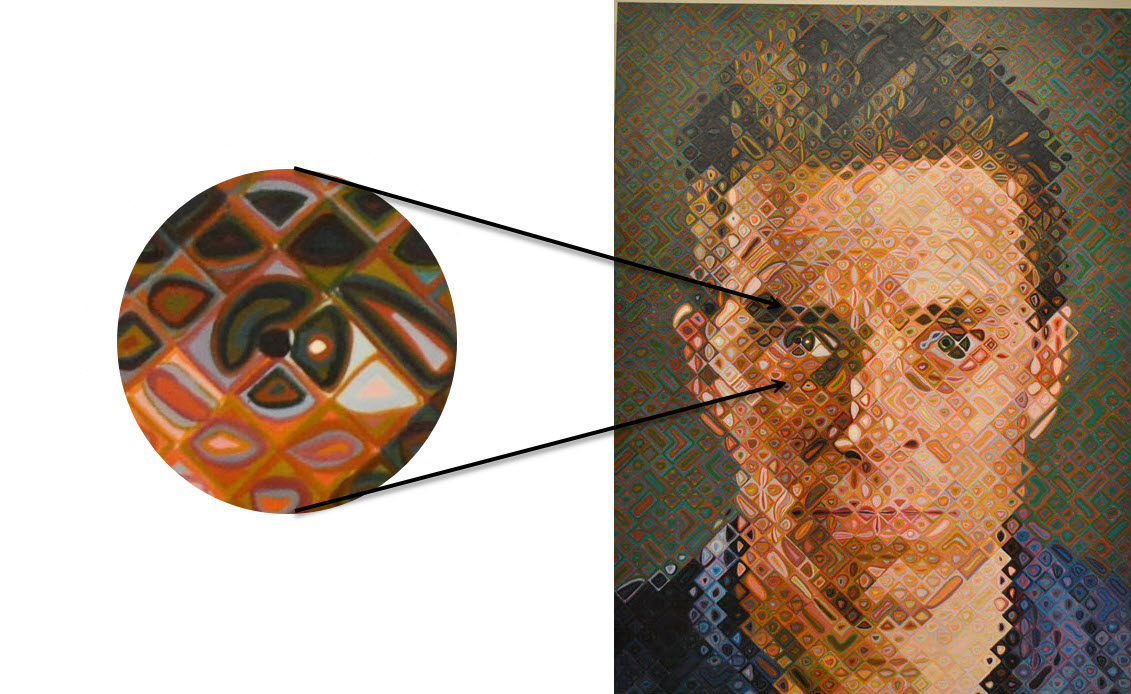

Up Close, Step Back

New learning is like viewing a Chuck Close painting. Up close, students see details like colors, lines, and shapes — the skills and facts of learning. As they step back to build context, the patterns reveal a bigger picture.

Learning that “organizes ideas into a conceptual framework…allows the student to apply what was learned in new situations.” (Donovan 13, Erickson et al. 11).

Moving close, seeing patterns. Stepping back, developing generalizations. Learning that transfers.

Designing for Transfer

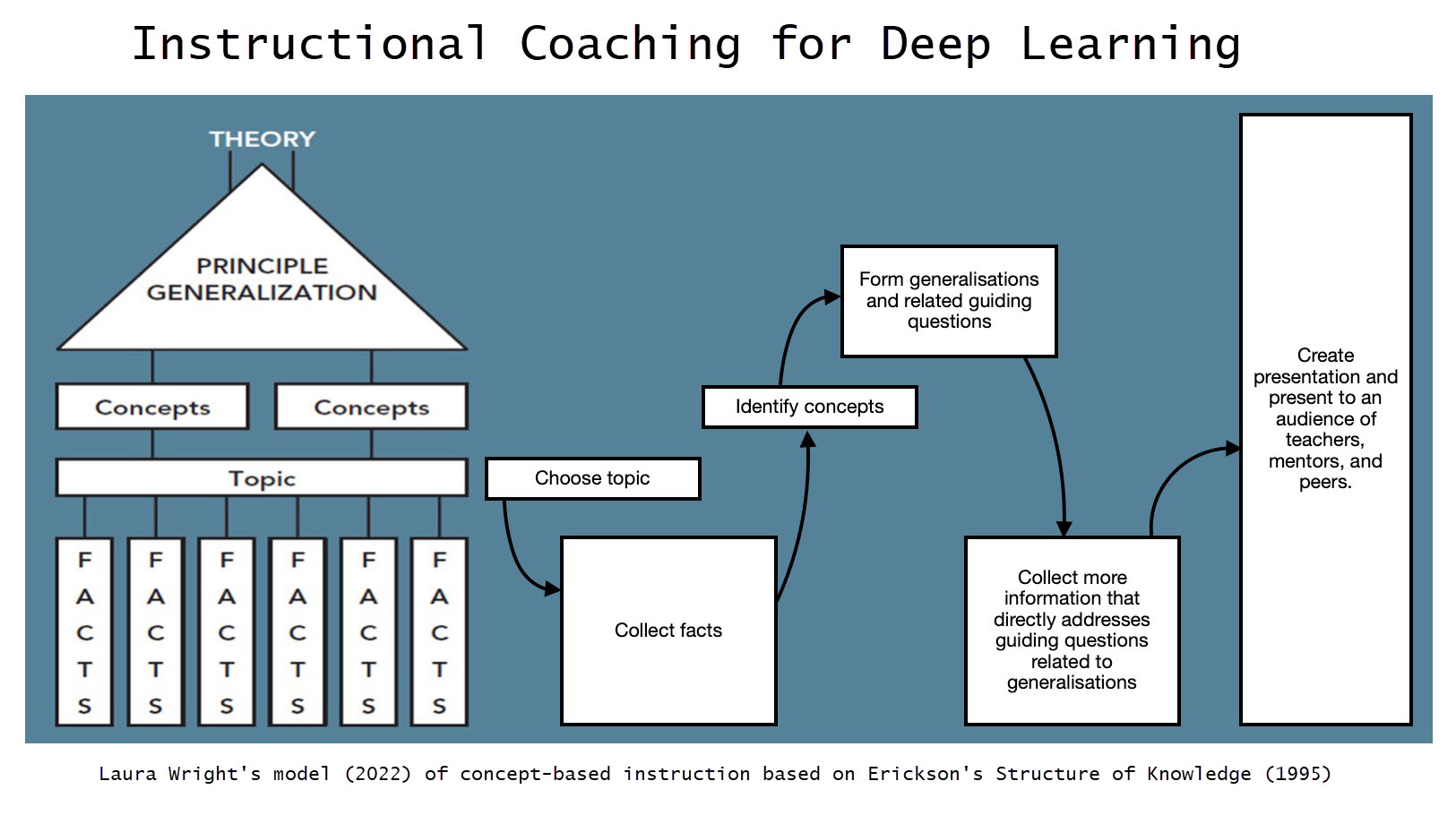

When students can connect their “personal stock of information, skills, experiences, beliefs, and memories” (Alexander et al. 317) to their learning, they become curious and motivated. Concept-based instruction structures learning to make real-world sense of facts by understanding them in context, organizing them into concepts, and synthesizing them into generalizations.

“Sticky learning reaches them not as assignments, lists of rules, and checklists, but as enthralling work — they experience information literacy as a transformational process” (Abilock 9-10).

Any process or format — from action civics or academic essays to annotated bibliographies — could be designed and taught for transfer. One inspiring example of concept-based inquiry research occurs during the IB Primary Years Program. Fifth graders are tasked with “identifying, investigating and offering solutions to real-life issues or problems” (PYP). Designed as a “collaborative, transdisciplinary inquiry process,” educators can teach subject-specific thinking skills and scholarly processes as meaningful — indeed indispensable. Students come to know that application, not accumulation, is the purpose of their investigation.

Research Begins with a Curious Classroom

Laura Wright, an international educator formerly at the International School of Amsterdam, and Helle Kirstein, the school’s Librarian, have designed an instructional sequence of near transfer activities (Perkins and Salomon 4) that will incrementally guide students towards the skills, processes, dispositions and performances needed for the project. Chief among them is inquisitiveness.

- Their classroom promotes curious dispositions “where students feel safe taking risks, making mistakes, failing, and not knowing or not being sure” (Jirout et al. 5).

- The teachers model curious behaviors by rewarding the exploration of uncertainties rather than a sprint to quick answers (Jirout et al. 6).

Teachers Plan and Troubleshoot

The teacher and the librarian identified “student independence and responsibility for their own learning” as their instructional goal and anticipated strategies that address potential challenges.

- How can we engage students in deliberate, critical curation instead of their normal rapid bookmarking?

- Given the wide range of topics and expertise, how might we organize our efforts so that each student develops adequate background knowledge?

- How can we make certain that the process of evaluation we teach to groups can be applied by every student during their individual research?

- Are there guardrails we ought to have in place as students identify sources on the open web?

- How can we teach the mechanics of citation as essential to independent research?

Teachers and Students Co-Create Knowledge

Laura created a collaborative project for each team’s topic in NoodleTools Starter. Unlike Project Inboxes where citations, notecards and other student work are submitted to teachers for review, this collaborative curation design allows teachers and students to co-create knowledge without discouraging student agency.

Acknowledging the range of students’ knowledge and experience, Laura explains how they allocated instructional responsibilities. “We did recognize that students would need significant support in learning how to confirm the quality of information. Initially Hella addressed this by teaching a general lesson on how to recognize a reliable website while I guided student searching of tertiary sources like BrainPop, Encyclopedia Britannica, National Geographic and National Geographic Kids. However, when we began identifying sources, it became clear that certain groups still lacked the background to judge their quality. To diminish their cognitive load, we decided to contribute ‘anchoring’ sources that could serve as models of quality. Since students had to read and decide to either accept or reject these sources, their fund of information began to grow and their critical capacity increased. As members of each group, we were able to monitor each student’s contributions and look for evidence of growing independent evaluation skills.”

NoodleTools Enables a Group Curation Process...

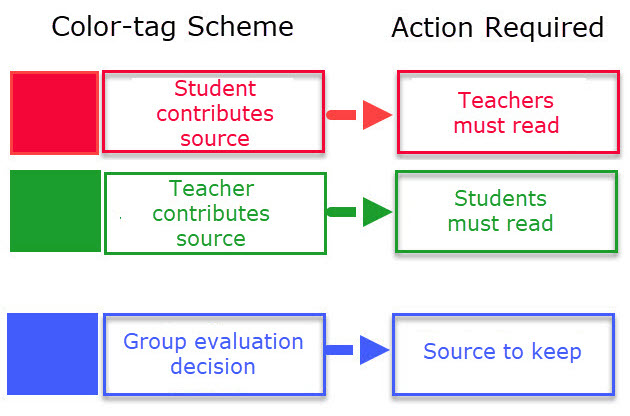

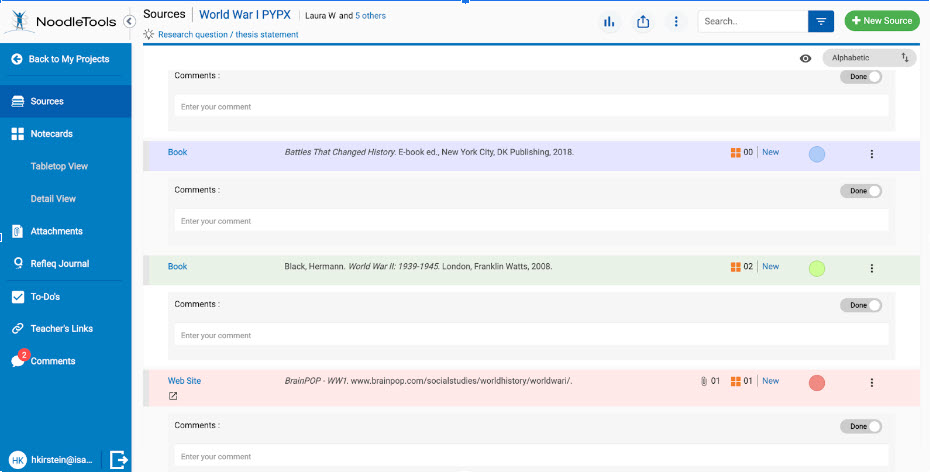

In NoodleTools one can color-code entries in the working bibliography. To reflect the stages of curation, each group’s entries were colored and recolored as they were identified and evaluated. Initially the color indicated the contributor: red for students, green for teachers. When teachers and students collaboratively decided that a source source was both relevant and credible, it was recolored blue.

...and Evaluation

By eyeballing the color-coding in this World War I bibliography, the group can quickly determine the status of their evaluation process.

- The first entry (blue) was accepted as a source by both students and teachers.

- The second entry (green) was suggested by the teacher for the students to investigate.

- The third entry (red) was added by the students but required a teacher’s confirmation. For purposes of assessment and feedback, teachers can identify who has contributed each source.

Transitioning Students to Analysis and Synthesis

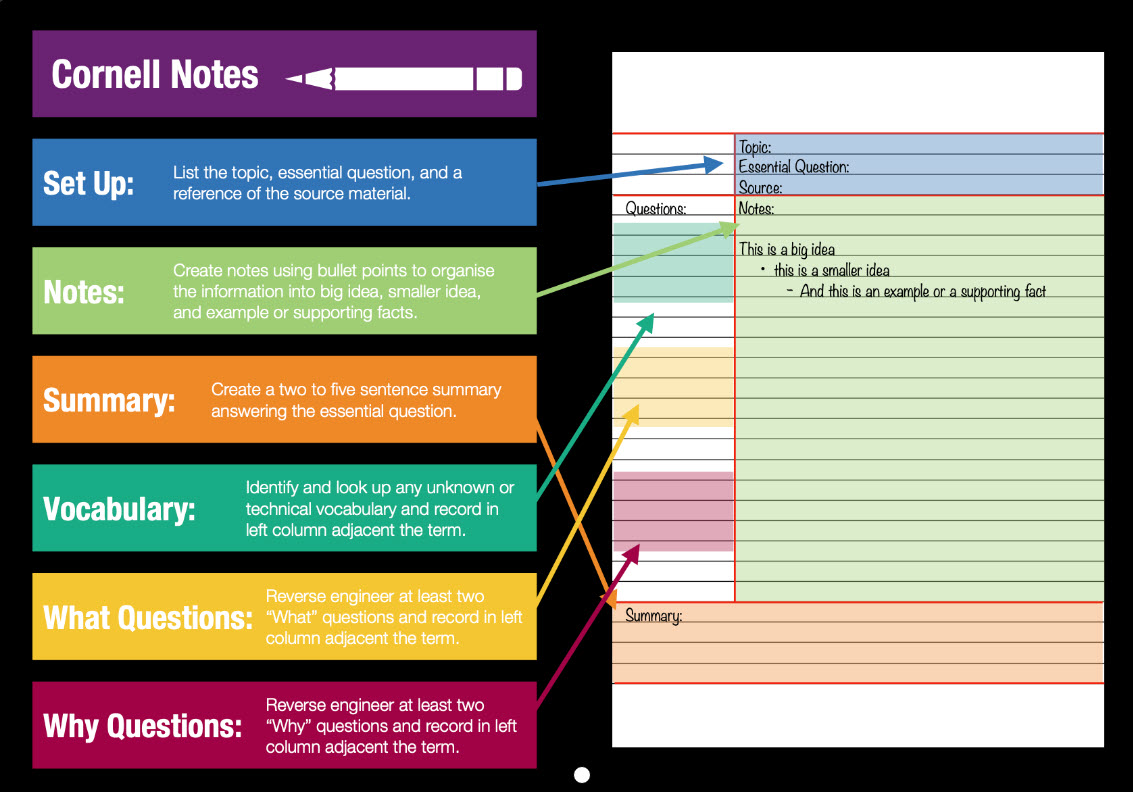

To help students read and analyze each source, Laura developed a modified Cornell Notes organizer which asked them to:

- Craft a 1-2 sentence summary of its scope

- Answer “what” and “why” questions that occur to them as they read

- Create a bulleted list of important ideas and supporting facts

- Define specialized vocabulary

- Translate foreign terms

This lays the groundwork for synthesizing information from multiple source ideas in NoodleTools notecards later.

Mining Sources and Experiences for Recurring Concepts

A collaborative concept-based research process requires that the group jointly arrive at a focus and craft relevant questions. At this point they return to review key sources in the group’s working bibliography and revisit their Cornell notes to find relevant evidence for their common questions.

Just as we learn to shift perspectives to appreciate a Chuck Close painting, students scrutinize information up close, then step back. Their goal is to uncover cross-disciplinary (e.g., systems, change) and discipline-specific (e.g., migration, plastics, audience) concepts related to the group’s focus. Key concepts can also be drawn from PYP and MYP documents and from their own knowledge and experiences.

Unique Contributions to the Group

This card bank about plastics pollution in the ocean) is composed of:

- Concept cards (gray) created by students and teachers

- Verb cards (green) created by the teachers.

Collaborative Creativity without Groupthink

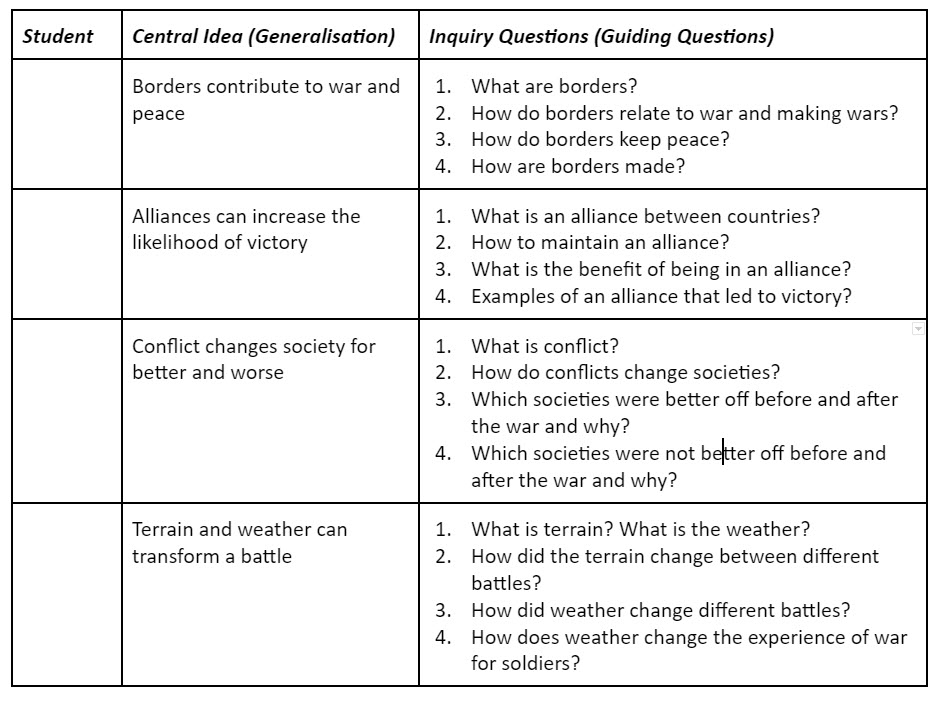

The teachers met individually with each student student to develop a separate research focus by combining concept cards into generalizations expressed as phrases. This anchored individual accountability and agency within the team. Then teachers met with each team to discuss their generalizations in order to arrive at a single central idea for their PYP Exhibition. The process facilitated group synergy while preserving individual creativity and agency.

demonstrating transfer learning

Next, students draft guiding questions for their own generalizations. These will guide their unique inquiry within the central idea.

By learning to conceptualize, generalize, and investigate ideas across time, situations, and among cultures (Stern, Ferraro, Mohnkern 2017, p.12), students are acquiring tranferrable skills, knowledge, and attitudes that will be reflected in their PYP Exhibition.

Organizing Collaborative Synthesis

working with multiple sources of information

Since a group typically amasses between 15 and 50 sources in a working bibliography, digital notecards are needed to support comparisons of diverse viewpoints and unique connections among multiple sources.

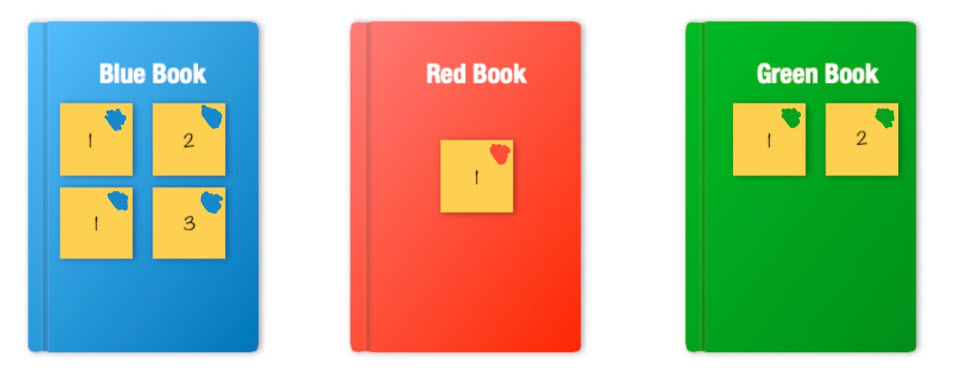

Using this visual to illustrated the process, Laura explains to students how NoodleTools notecards can scaffold the group’s sorting:

- Sources (shown as blue, red and green) contain ideas (yellow) that answer guiding questions.

- Each student extracts an idea from their curated sources onto one NoodleTools notecard and titles it with the guiding question to which it relates. This process is repeated until all relevant information has been recorded on notecards.

- Notecard titles are numbered consecutively to differentiate contributions to the same question.

- When the group piles notes by question, information extracted from different sources can be compared and evaluated.

In NoodleTools, the note is always linked to the source (represented in the visual by a dot of color on each card) so that a student will be able to refer back to ideas in context or verify a quote, when necessary. Of course, they also can be confident that information will be correctly attributed.

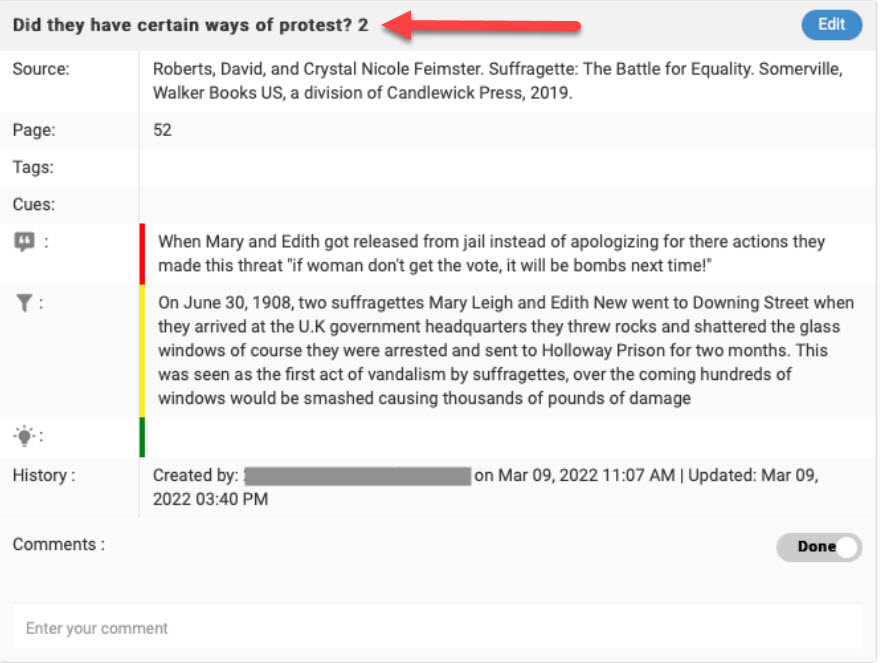

The Early Suffragettes group can see that this is the second notecard created for one of their questions. Titled this way, notes extracted from different sources can be organized by a single question but distinquished by a unique number.

Teacher’s insights

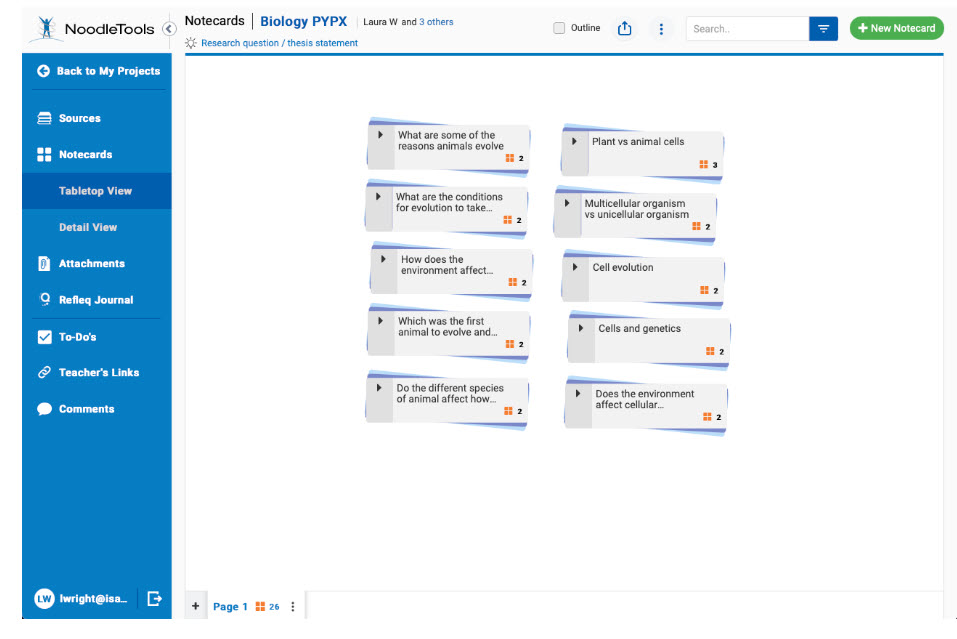

“The groups discovered the ability to make piles and sorted them in rows by team members. “When everyone’s work is visible by each contributor, it makes group members accountable to each other,” Laura remarks.

“In the future, I’ll suggest that groups use NoodleTools’ paging function to create separate pages for each member of the team once the number of notecards becomes too cumbersome for a single page.”

A Snapshot of Conceptual Learning in Action

“Groups of students are scattered around the room developing their 5th-grade Exhibitions. The Ocean Pollution group is planning a small-scale model to demonstrate innovative trash collection being used in Amsterdam’s canal systems. The Book Cover Design group is visually analyzing Harry Potter book covers from different countries and time periods. The Sharks group is crafting multiple-choice questions in order to digitally collect people’s perceptions of the fish as both a man-eater and human food source. The Biology group is researching genetics in the library in order to create a diagram that demonstrates how cystic fibrosis is passed from one generation to the next. The Early Suffragettes group is browsing archival photographs of suffrage marches to locate ones that will help them design costumes for their presentations, then adding citations to their NoodleTools project. The World War I group is composing a formal letter asking their parents to take them to a special museum in Belgium explaining why it relates to their study. The Mathematics group has located a history of Pi and is devising a demonstration of the concept using pizzas. Students exhibit curiosity, creativity and agency when they own their learning.”