Throughout my time in the classroom, I’ve seen that paraphrasing is one of most confusing concepts for students to master. That’s why I developed a four-step process called micro-paraphrasing over the last nine years as a teaching librarian working with middle school and high school students at all ability levels.

Micro-paraphrasing is part of the plagiarism education program described in my comprehensive instructional handbook, Combating Plagiarism: A Hands-On Guide for Librarians, Teachers, and Students (Table of Contents).

“Put it into your own words”

There is a lot of misinformation about paraphrasing. Part of the confusion comes from how we define paraphrasing and the various recommendations we make about how to do it. Summarizing is a useful tool for synthesizing information for purposes such as notetaking. Paraphrasing is a useful for condensing “wordy” sentences into a concise restatement of an idea that can be used as evidence in a research assignment.

Actually it’s quite difficult to read several sentences, understand the intent and paraphrase it without plagiarizing. Students wonder:

How much of the original should I change?

Which words can be reused?

Why do I need a citation or footnote since I’m writing a new sentence?

How long should the paraphrase be?

Micro-Paraphrasing Instruction

I developed micro-paraphrasing to clarify and streamline the task of restating an author’s words. It’s a two-sentence approach emphasizing reading comprehension — ethical information synthesis — in which students use fewer sentences and carefully chosen language to amplify the accuracy of their paraphrase.

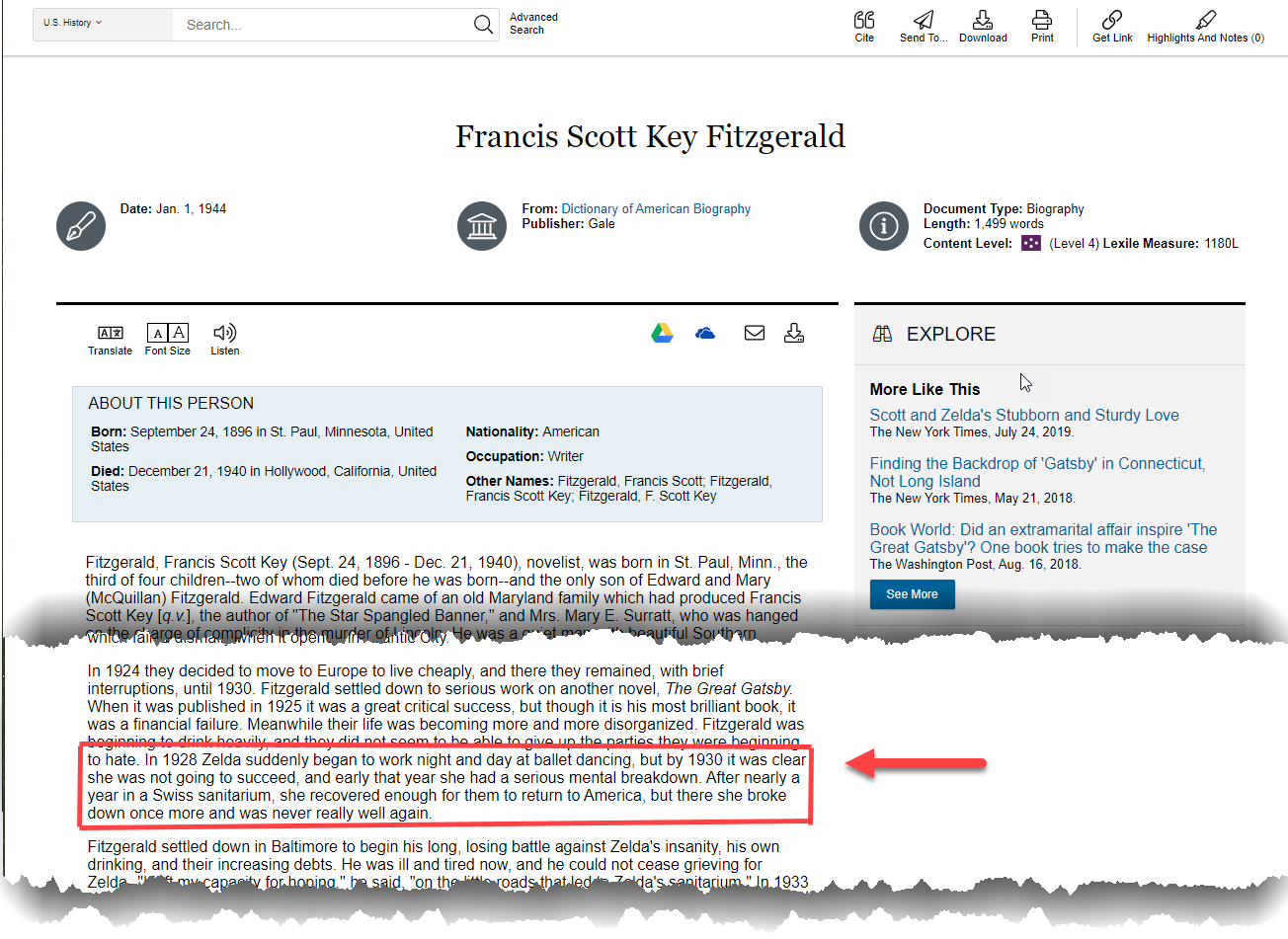

Instruction begins with a digital source chosen from a subject area students are investigating. I project the two sentences and the citation and lead students through each step of micro-paraphrasing. We wrestle with alternative rewording and language choices together.

Then students test their understanding of micro-paraphrasing by practicing on additional examples that I give them on a paper handout. Using a workshop approach, I circulate as they practice, offering individualized help and reviewing the steps as needed. When a student’s idea or my advice could benefit everyone, it’s shared with the entire class. In subsequent classes, I will briefly review the micro-paraphrasing steps before we begin work. Once I feel confident that students have grasped the process, they’re expected to choose their own two sentences from a paragraph on a web page or from a research database and digitally mark them up using computer pens.

A teaching example

The sentences I’ve chosen below are from a reference article without an author in the Gale in Context: U. S. History research database. I selected two adjacent sentences so that the ideas are related. Typical of biographical reference sources, they contain important information but are more verbose than what students need for their own writing task, making them ideal for this exercise.

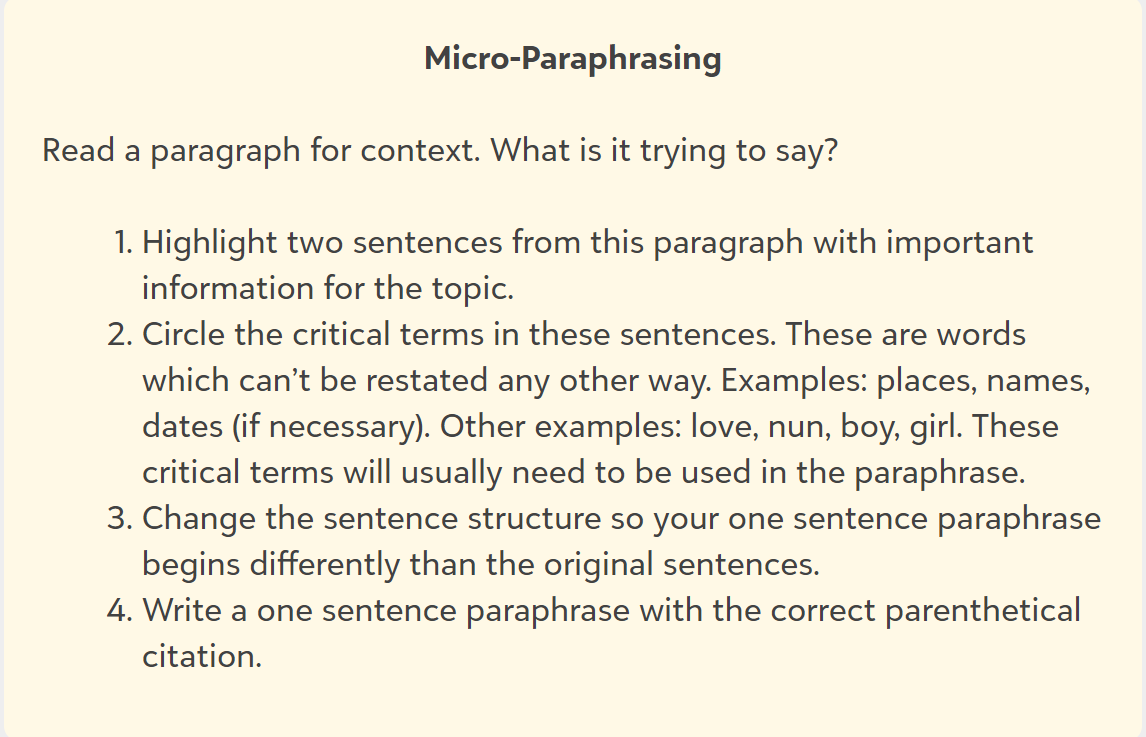

The Four Micro-Paraphrasing Steps

- Read the two sentences out loud with comprehension in mind. Prompt students to ask themselves: What is this trying to say? You may be surprised at student responses to this question. Many read digital information too quickly to absorb the idea. It may take several minutes of discussion for students to understand that ethical paraphrasing always begins with understanding the author’s idea and intent. Encourage students to create an “imperfect” initial verbal restatement of the main idea. In this example, the sentences are trying to say that while working towards a ballet career, Zelda struggled with mental health problems and never recovered.

- Find critical terms in the original sentences. Critical terms are words and phrases in the original sentences that cannot be restated any other way. Names, dates, and places are the most obvious critical terms students should notice. Critical terms are the only words from the original sentences that should be considered for reuse in the paraphrase. It’s not mandatory to reuse all the critical terms, but everything else in the sentences should either be restated or disregarded. I have noticed that, when students circle the critical terms by hand, it isolates those words and reinforces the key idea. The critical terms are 1928, 1930, Zelda, ballet, Swiss, mental, and America.

- Decide on a new structure for the paraphrase. The benefit of only using two sentences is that it makes it easier to visually show how the paraphrase can restructure and compress an idea. The first sentence explains that Zelda is preoccupied with ballet dancing but her limitied aptitude may, in fact, have contributed to her breakdown. The second sentence elaborates on her psychological state. One alternative structure would be to begin the paraphrase by describing Zelda’s mental health problems.

- Write the paraphrase with a citation or footnote. This important, last step is not intuitive. Students will need to be prompted to use a citation or footnote for each practice paraphrase.

My Micro-Paraphrase

Alternative paraphrase:

Zelda experienced lifelong mental health problems after a failed attempt at ballet from 1928-1930 (“Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald”).

Here’s an explanation of my choices:

- Even though Swiss is a critical term, the fact that she stayed in a Swiss sanitarium is not important enough to the essential meaning to be included in the paraphrase.

- I chose lifelong to concisely restate the idea that she experienced at least two mental breakdowns and was “never really well again.”

- I converted the years to a range to concisely represent the timeframe given in the initial sentence.

- By the time students have read this article, they should already know that Fitzgerald lived in America and, as common knowledge, the country can be omitted.

Since this skill should be practiced during each school year, especially during the research paper process, students can quickly locate the step-by-step instructions on my library’s website (seen in the screenshot on the left).

Micro-paraphrasing helps students use secondary-source information more effectively. It focuses students on the main idea and helps them create a concise, ethical synthesis of information for their research papers.

Terry Darr is library director at Loyola Blakefield, an independent college preparatory school for boys in grades 6–12. She teaches more than 200 information literacy classes each school year. The last ten years have taught her how to design instruction that works for her students. She is a regular book reviewer for ALA and Library Quarterly. Darr has presented on plagiarism education and micro-paraphrasing in the Maryland and DC areas. She can be contacted at darrterry@gmail.com.

“Combating Plagiarism is a coherent and detailed instructional plan for plagiarism education which positions the librarian as a resource for middle- and high-school students and their teachers, as well as school administrators.”