From Working to Winning

A working bibliography contains sources that students thought they might use, some of which are now redundant. Before submitting a paper or project, here’s how students can cull marginally relevant “fool’s gold” in order to create a final works cited list that reflects their best thinking.

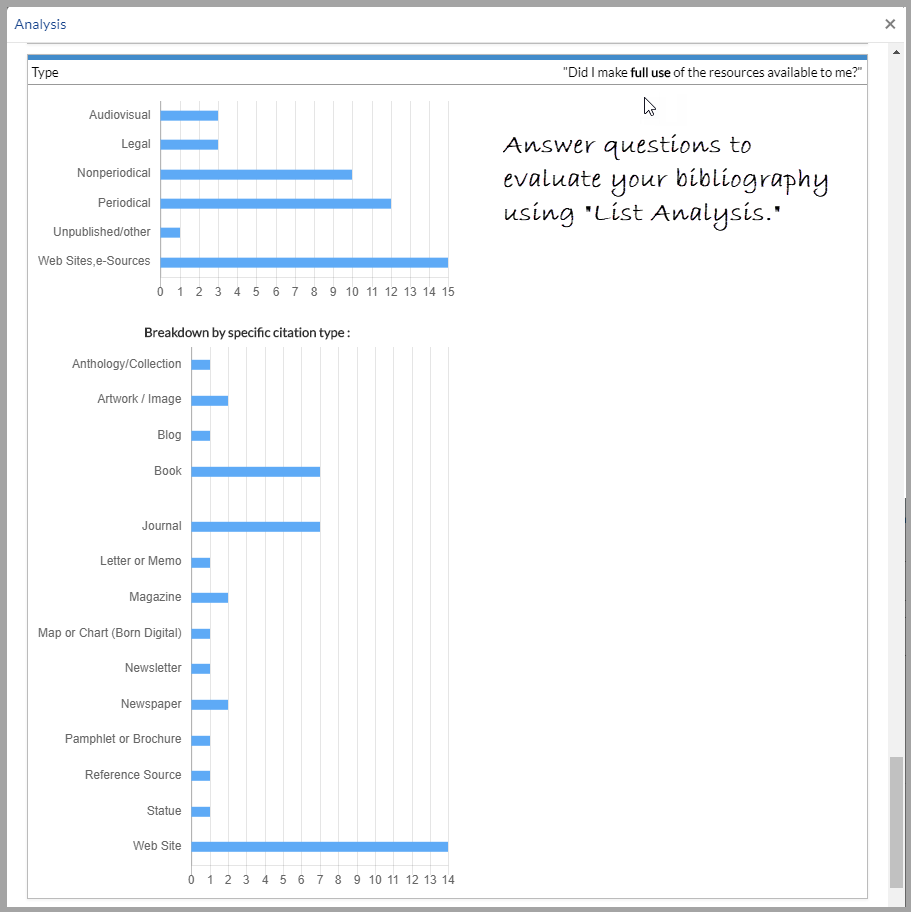

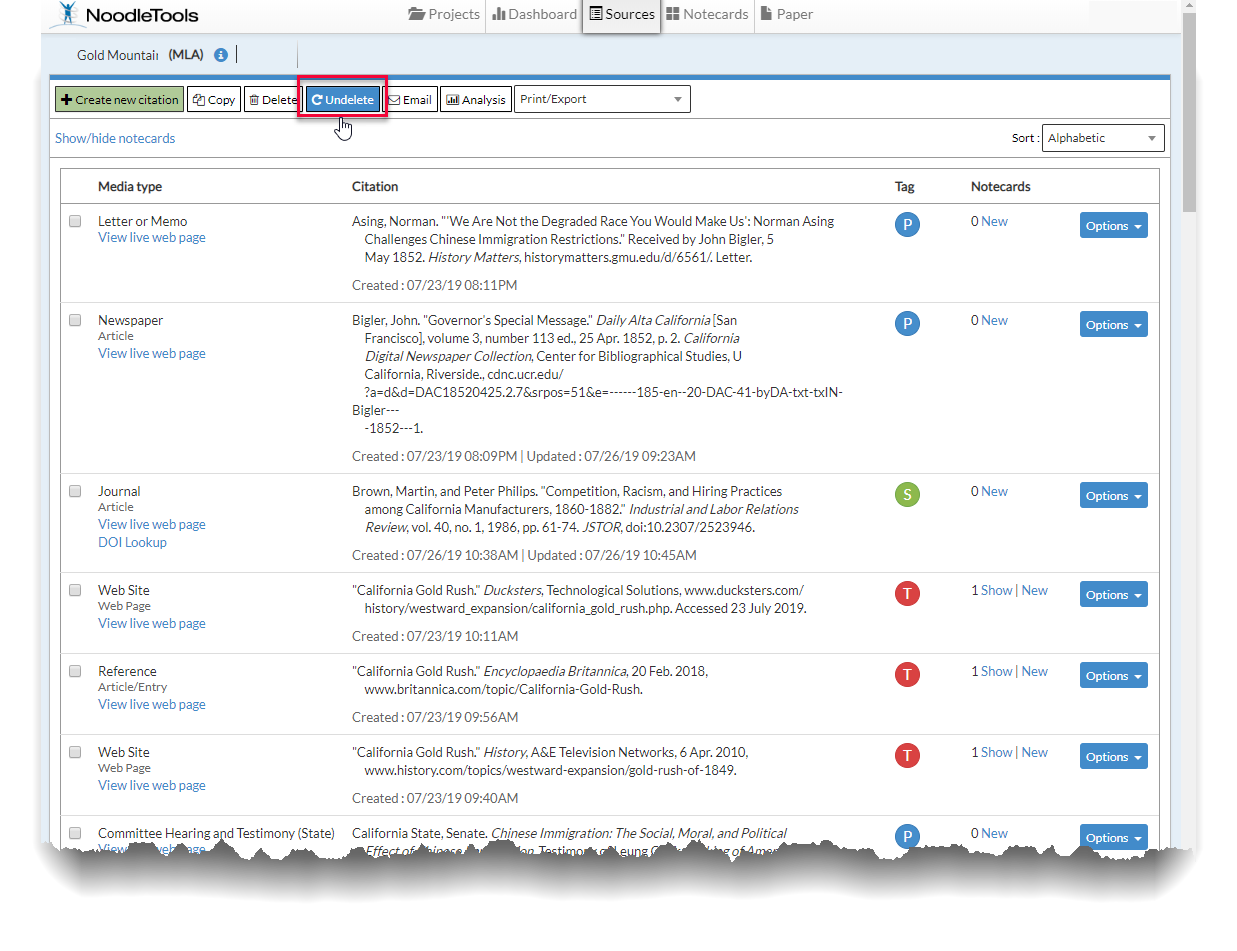

For a quick initial evaluation, use NoodleTools’ “List Analysis” which aggregates data about entries by publication format and date, and type of resource. As a result, you can overview attributes like currency and balance in order to assess a list holistically.

This screenshot shows some of the data gathered when you use this feature.

Tip: There’s still time to fill a gap!

Now Go for the Gold!

To Begin, Label Primary, Secondary and Tertiary Sources

First organize sources by labeling each entry as primary (P), secondary (S) or tertiary (T). Sorting by categories enables you to compare sources that are similar in purpose, perspective or time and place.

Step 1: review Tertiary Sources

A tertiary source digests or summarizes a topic. Encyclopedias, dictionaries, textbooks, guides and handbooks distill, summarize and provide background, predictably rehashing common knowledge. Identify the most comprehensive and relevant tertiary sources and delete the rest.

Teaching tip: Download http://noodle.to/goldtertiary which contains sources that have basic information about the California Gold Rush. Click “Show/hide notecards” to reveal pre-created notecards about immigrants to California. Ask sudents to determine the best tertiary source and explain their reasoning in the annotation field. After that, they can share this project with you for feedback and discuss their choices in class.

Step 2: Compare Primary sources

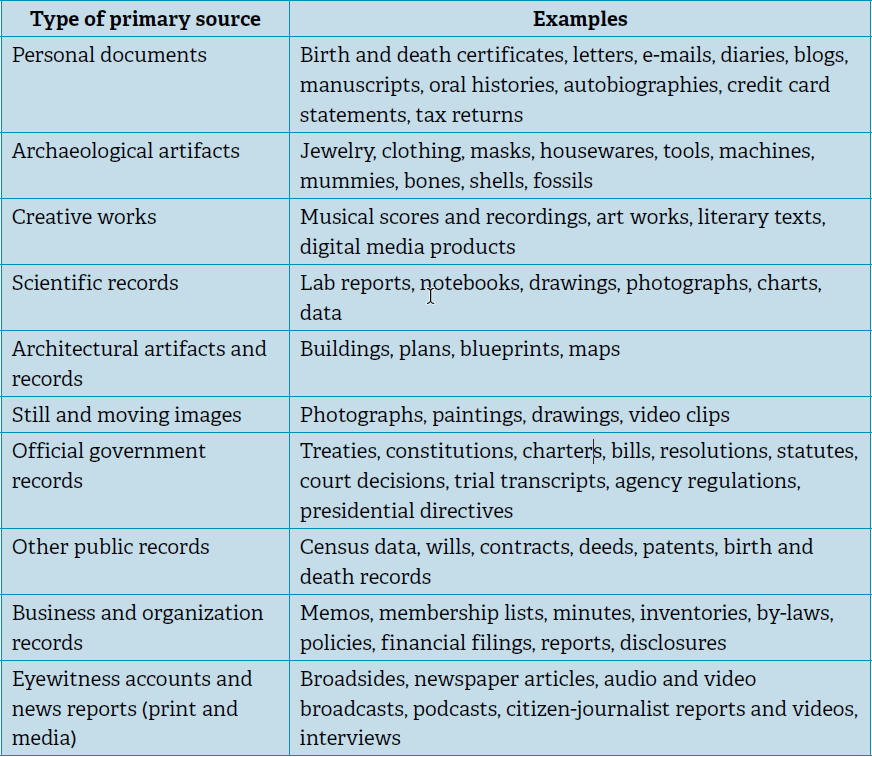

Primary sources are the surviving records of a period, eyewitness accounts, and original reports of research. They’ve been created by individuals, teams, organizations, governments, cultures and by the natural world itself.

Like shells that are washed up on the beach, primary sources leave traces — an incomplete picture of what happened in the past. However, they’re rich and varied and will stimulate curiosity and original thinking.

Reprinted from Debbie Abilock's Adding Friction column "Is This a Primary Source?" in Library Media Connection, October 2013, 54-55.

Teaching tip: Students can practice comparing two similar primary sources.

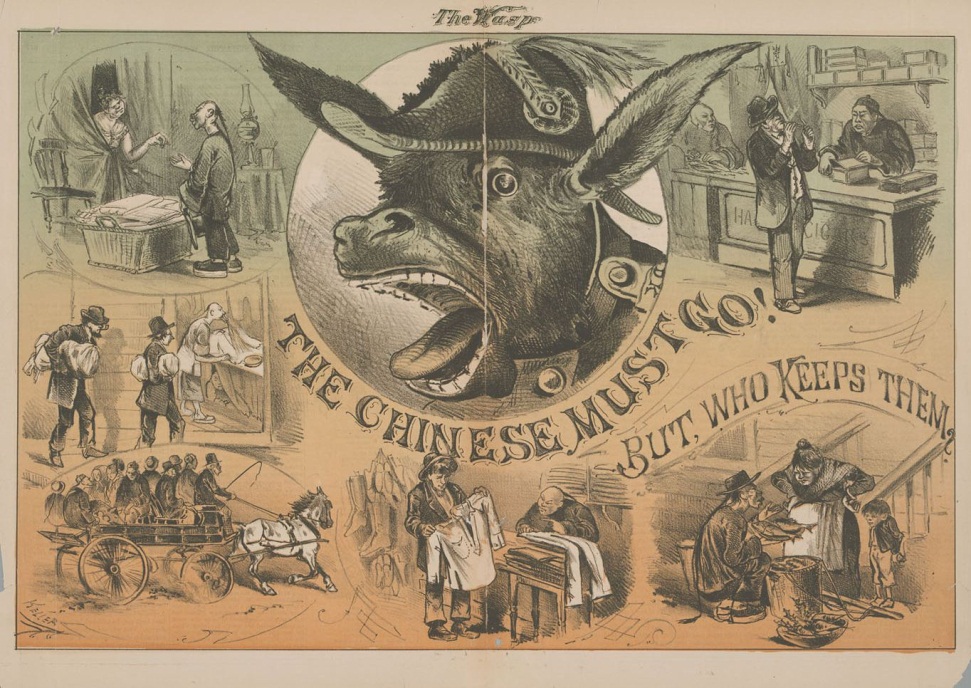

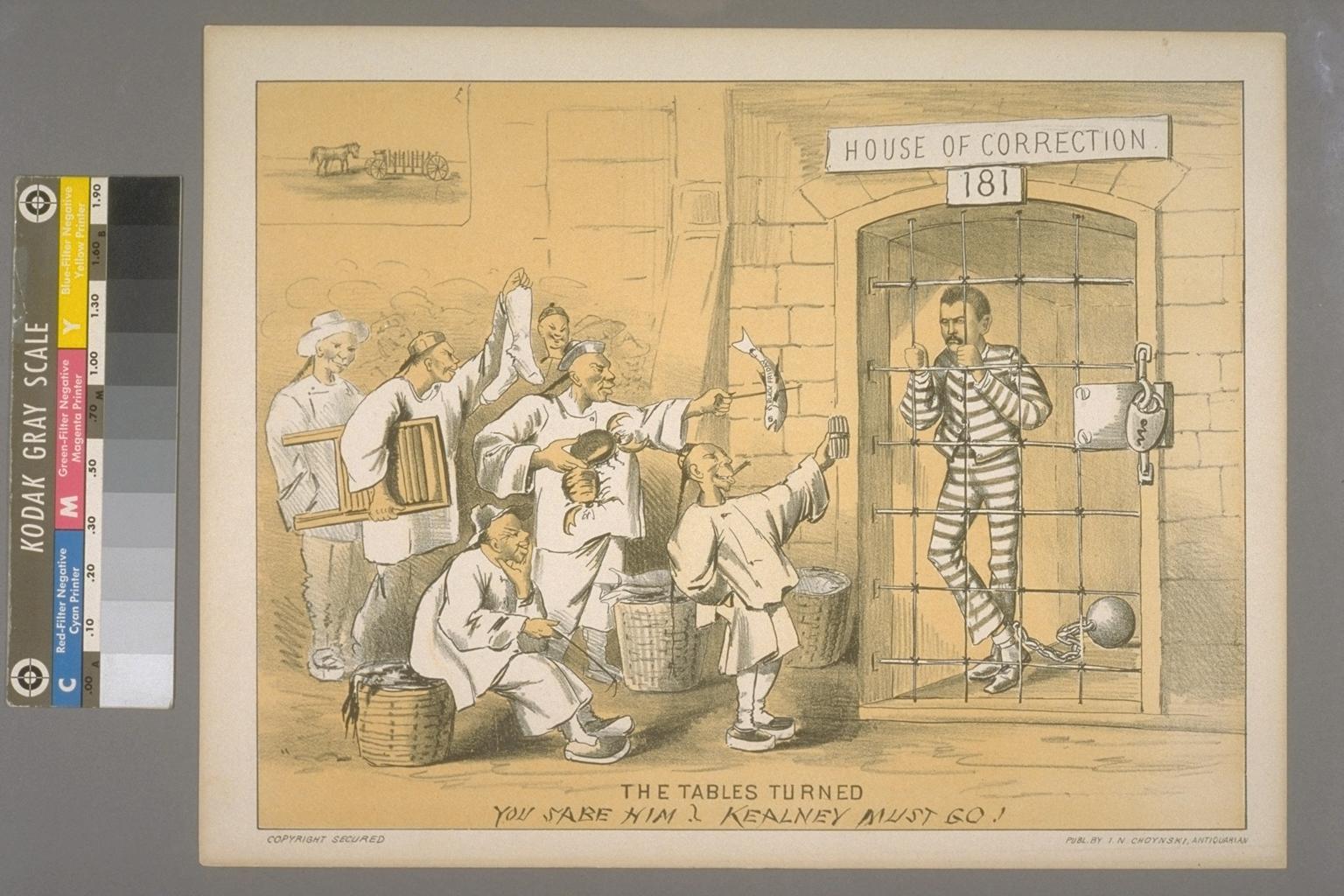

The two political cartoons below were published at about the same time. Ask students to imagine researching attitudes toward Chinese immigrants. For instance, do they share the same tone? Reflect the same point of view? In other words, how do they contribute to our understanding of the problem?

Available at Online Archive of California,

What is the unique value of each primary source? For instance, does it…

- Recreate a sense of time and place (e.g., video, photo, drawing, map)?

- Reconstruct how people thought or felt at the time or what motivated them (e.g., editorial, diary, interview, political cartoon)?

- Articulate an institution’s position firsthand (e.g., treaty, press release, court decision)?

- Reveal a researcher’s methods or measurements (e.g., lab report, scientific paper, data)?

Step 3: Evaluate secondary Sources

A secondary source interprets evidence gleaned from primary sources. The writer proposes a theory or creates a story about why and how something has happened in the past, discussing and critiquing the ideas of scholars and other experts. Examples of secondary sources include biographies, histories, and journal or magazine articles.

Students develop confidence and voice when they master the evidence, reason with their sources and craft their own story. They are building a polished bibliography for their own secondary source — a new contribution to the scholarly conversation.

A Thoughtful Pattern

“History is not the past. It is what historians and other historical thinkers make of the past.”*

*Teaching for Historical Literacy: Building Knowledge in the History Classroom by Matthew T. Downey and Kelly Ann Long, Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, 2016, 25.

Photograph credit ©Maria Abilock

Resources for Teachers: 19th Century Views of Chinese Immigrants

The resource lists accompanying this blog entry cover Chinese immigration to California during and just after the Gold Rush (1848 – ). To use these MLA works cited lists in your own teaching, click the links below to download them to your NoodleTools account:

Primary resources: http://noodle.to/goldprimary

Secondary resources: http://noodle.to/goldsecondary

Tertiary resources: http://noodle.to/goldtertiary